|

|

Legal Corner: Drafting Ordinances with Clarity

By: William Bock, General Counsel, League of Arizona Cities and Towns

By: William Bock, General Counsel, League of Arizona Cities and Towns

June 2013

Last month I wrote an article about the powers and authority of cities and towns. I noted that sometimes the statutes that grant

a power to a city or town are not written very clearly. That often results in lawsuits and ultimately a court will have to decide

what the legislature meant when they adopted their laws.

It seems like that is the worst of all possible worlds; a court trying to figure out what the legislature meant instead of just

writing the law clearly in the first instance. That is not in the best interests of the state, or in the case of ordinance, not

in the best interest of cities and towns.

Shortly after I was hired at the city of Phoenix Law Department, the city attorney created an Ordinance Review Committee ("Committee").

The committee was created because the city prosecutors had been complaining about trying to enforce city ordinances. The prosecutors

were heard to say very often, "I wonder what those attorneys on the civil side were smoking when they wrote this ordinance?" The

purpose was to get a group of attorneys, prosecutors and civil attorneys to sit down and go over drafts of the ordinances before

the city council adopted them. We would look at things like clarity, legality, constitutionality and enforceability. We would iron

out the wrinkles in the committee, which would hopefully result in an ordinance that was clear, concise and easy to enforce.

I became the chairman of the committee in 2000, and remained in that position until I retired in 2011. During that time we had numerous

meetings, reviewing many different ordinances such as building code, zoning, historic preservation, adult business, nuisance prevention,

etc. Our process required a department, like planning and zoning, or the department's attorney to draft a proposed ordinance for our

review. Each of the attorneys on the committee would review the ordinance before the meeting.

The department that drafted the ordinance and the department's attorney were then invited to a meeting of the committee. At the beginning

of each committee meeting, I would tell the staff from the ordinance drafting department that our attorneys had reviewed their draft, but

before we got started, I would always ask them to tell me in their own words what they were trying to accomplish with the ordinance. After

their explanation, I would venture a guess that more often than not, I would say to them, "I understand what you just told me you were

trying to accomplish with your ordinance, but the ordinance doesn't say what you just told me."

Usually after I said that, the people were either astonished or angry at my suggestion that the ordinance was not well-written. However,

after going through the ordinance line by line, and sometimes word by word, and discussing the meaning of the word or sentence, the department

staff usually understood how what they had written meant different things to different people.

Let me give an example of what I am talking about. Let's suppose this is a sentence in an ordinance. "Bill saw Judy driving down the street."

You should have written "Bill, while driving down the street, saw Judy" unless you meant "Bill saw Judy, who was driving down the street." As

you can see, depending on how you write that very simple sentence, either Bill or Judy was driving down the street. The writer knows what was

meant, but the reader does not.

If that had been a sentence in an ordinance, how would the reader of the ordinance know what the city or town council meant? How would the

prosecutor know?

During my time on the committee, I encountered many examples like the one above. One particular ordinance sticks in my mind, but instead of

sentence structure problems, it involved an ambiguous word. The planning and zoning department wanted to amend the single family housing

portion of the zoning ordinance. They wanted to make sure that neighborhoods were not, as the song goes, "all made out of ticky-tacky and

they all look just the same."

They drafted an ordinance requiring that homes built in a neighborhood should not be "monotonous." Because this was an ordinance, it meant

that if adopted, someone on staff would have to decide what "monotonous" meant, and depending on their personal definition, a citizen may or

may not be granted a permit.

When confronted with this ordinance, our committee raised the issue of the meaning of "monotonous." The planning staff then said, after quite

a bit of prodding, that they meant that houses next to each other shouldn't have the same front elevation; that they should not be in the same

color family; and that they should not have the same roof material or roof pitch. That provided meaning to everyone-the citizen and the

enforcement and permitting staff. So I said, "Then let's write the ordinance the way you just described it to me." That became my motto-write

what you mean. Don't assume everyone else knows what was in your head.

In recent article in the International Municipal Lawyers Association magazine, attorney Kimberly Mickelson wrote an article entitled "Drafting

Regulations: The Power of Clarity." (IMLA, March/April 2013.) In the article she recounted a court case where an ordinance had been drafted as

follows:

"All parking lots serving commercial land uses shall provide green space equivalent to 30% of the required paved parking area."

The goal of the ordinance was to increase the amount of landscaped, grassy, treed areas. One property owner balked, and then painted an additional

30% of the paved area green. The judge agreed with the property owner; "green space" was not defined, and the ordinance as written didn't address

landscaping or trees.

When you are preparing to draft an ordinance, the first thing you should do is think through very clearly what it is you are trying to accomplish.

Make sure you do not use words that are vague. And do not make assumptions that everyone will know what you mean. Spell out what you mean clearly

and simply so that that you have reduced the chance that someone else will read the ordinance differently.

Another pitfall in drafting ordinances is having different sections of the same code seemingly conflict with each other. For example, one ordinance

may use a term "city limits," while another ordinance in the code may use the term "municipal boundaries." Do they mean the same thing? Or was there

an intended difference?

Once an ordinance has been adopted, if the meaning of an ordinance is brought into question, like the "green space" example above, a court's primary

goal is to ascertain the intent of the town or city council. If they cannot tell from the plain words of the ordinance, then they use what is called

"canons of statutory construction." One example of a canon is that if there are two ordinances that seem to conflict with each other, the court will

assume that the city council knew of the existence of both sections, and will try to give meaning to both sections. If they cannot, sometimes they will

assume that the ordinance that was adopted last must be what the council wanted the ordinance to say. If you don't want the court engaging in these

types of mental gyrations, then drafting clearly in the first instance is best. You should also be aware of other provisions in your city code to

avoid writing ordinances that conflict with each other.

There are several other legal consequences of poor drafting. One is called "standard less delegation of authority." That means that a city council

cannot adopt an ordinance like the "monotonous" example, and then expect that the planning staff will figure out what that means. Courts will declare

such an ordinance invalid, because the city council has given staff its legislative authority to decide what "monotonous" means. That could result in

one decision one day, and a different decision on another day. What the ordinance must have is standards for the staff to follow. In our example, it

would be to make sure that two houses next to each other are not in the same color family, or do not have the same front elevation. In that case, the

regulation is adopted by the policy makers (the city council) and carried out by the staff.

"Although municipal regulations are imposed in order to promote health, welfare, safety, and morals, it is necessary that their exactions be fixed with

such certainty that they are not left to the whim or caprice of an administrative agency. . . . Of course, so long as the local legislative body

establishes a policy and fixes standards for the guidance of administrative agencies, the grant of power is constitutional." McQuillin, The Law of

Municipal Corporations, § 18.11

Another legal consequence of poor drafting is when a criminal ordinance is vague. The law is clear that a person who is governed by an ordinance should

not have to guess as to how to control conduct to comply with the ordinance. If the person has to guess, then the ordinance is most likely

unconstitutionally vague, and it will be struck down by a court. For example, Papachristou v. Jacksonville and Kolender v. Lawson were two Supreme

Court cases where the court struck down laws against vagrancy for unconstitutional vagueness; in restricting activities like "loafing," "strolling,"

or "wandering around from place to place," the law gave arbitrary power to the police and, since people could not reasonably know what sort of conduct

is forbidden under the law, could potentially criminalize innocuous everyday activities. Also, in Gatto v. County of Sonoma, 98 Cal. App. 4th 744, 120

Cal. Rptr. 2d 550 (1st Dist. 2002), an ordinance was declared invalid for vagueness where the ordinance established a dress code prohibiting wearing of

"gang colors."

"An ordinance must be clear, precise, definite, and certain in its terms, and an ordinance vague to the extent that its precise meaning cannot be ascertained

is invalid . . . The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States requires that a city ordinance must be definite

and certain in its statement of prohibited conduct to enable persons of ordinary intelligence who read the ordinance to understand what activity is proscribed

and govern their actions accordingly." McQuillin, The Law of Municipal Corporations, §15.22.

The best way I have determined to make sure that ordinances are written as clearly as they can be, and that they actually accomplish the desired result, is to

have a group of people review and discuss the ordinance. It helps to have your city attorney involved in those discussions, but simply asking other people who

are reading it for the first time and who have not been involved with the drafting can be useful. It is a fresh set of eyes, and very often they will read an

ordinance differently than the drafter. Then there needs to be a discussion, and rewrite the ordinance so that it is not susceptible to more than one

interpretation.

It is almost impossible to achieve perfection. The English language is often not precise. But we have to do the best we can so our ordinances regulate in the

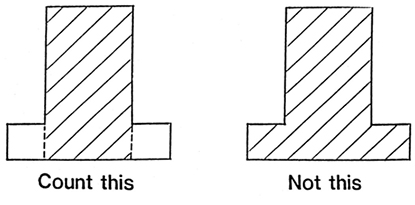

way we intended. Sometimes, even a picture or drawing helps explain. A picture is worth a thousand words. Here is an example from a zoning ordinance

regulating the area of wall signs erected over 56 feet. The regulation, in words only, is somewhat confusing, but becomes clearer with the use of diagrams:

Area. The area of a wall sign erected over fifty-six feet in height shall not exceed one percent of the area of the elevation to which it is attached. This

area shall not be increased through a comprehensive sign plan and shall not be counted against the wall signage which may be placed on the building below

fifty-six feet. This provision is illustrated in the graphic below:

Signs Erected Over 56 Feet

Signs Erected Over 56 Feet

In conclusion I have two suggestions for drafting ordinances or ordinance amendments. First, it would be to think it through. Make sure you understand

exactly what it is you are trying to accomplish, and then put it into words as plainly and simply as you can. Don't assume that others know, or even

understand what you know, or what is in your head. You should write your ordinance for an audience that knows nothing about your subject matter. If you

do, then you are on your way to an ordinance with clarity. If you have to define terms to provide a better understanding, then you should do that.

The ultimate goal is to have a clear, legally enforceable ordinance that anyone can read and understand. If done correctly, there is no reason for a court to

have to guess at what you meant in an ordinance.

Second, involve your municipal attorney. In addition to clarity, there are many other legal issues involving ordinances which must be considered. Your attorney

can guide you through these issues. And your attorney is trained at reading words and interpreting language. Your attorney can help you write your ordinance

clearly the first time, so that someone else, including a court, will not have to interpret what you or your council meant by an ordinance.

Next month, we will have an article on how to effectively use your municipal attorney.

|

|

League of Arizona Cities and Towns

1820 W. Washington St.

Phoenix, AZ 85007

Phone: 602-258-5786

Fax: 602-253-3874

http://www.azleague.org

|

|

|